SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

_________________

No. 21-869

_________________

ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, INC., PETITIONER

v. LYNN GOLDSMITH, et al.

on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals for

the second circuit

[May 18, 2023]

Justice Kagan, with whom The Chief Justice joins,

dissenting.

Today, the Court declares that Andy Warhols eye-popping

silkscreen of Prince-a work based on but dramatically altering an

existing photograph-is (in copyright lingo) not "transformative."

Still more, the Court decides that even if Warhol's portrait were

transformative-even if its expression and meaning were worlds away

from the photo-that fact would not matter. For in the majority's

view, copyright law's first fair-use factor-addressing "the purpose

and character" of "the use made of a work"-is uninterested in the

distinctiveness and newness of Warhol's portrait.17 U. S. C.

§107. What matters under that factor, the majority

says, is instead a marketing decision: In the majority's view,

Warhol's licensing of the silkscreen to a magazine precludes fair

use.[

1]

You've probably heard of Andy Warhol; you've probably seen his

art. You know that he reframed and reformulated-in a word,

transformed-images created first by others. Campbell's soup cans

and Brillo boxes. Photos of celebrity icons: Marilyn, Elvis,

Jackie, Liz-and, as most relevant here, Prince. That's how Warhol

earned his conspicuous place in every college's Art History 101. So

it may come as a surprise to see the majority describe the Prince

silkscreen as a "modest alteration[ ]" of Lynn Goldsmith's

photograph-the result of some "crop[ping]" and "flatten[ing]"-with

the same "essential nature."

Ante, at 8, 25, n. 14, 33

(emphasis deleted). Or more generally, to observe the majority's

lack of appreciation for the way his works differ in both

aesthetics and message from the original templates. In a recent

decision, this Court used Warhol paintings as the perfect exemplar

of a "copying use that adds something new and important"-of a use

that is "transformative," and thus points toward a finding of fair

use.

Google LLC v.

Oracle America, Inc., 593 U. S.

___, ___-___ (2021) (slip op., at 24-25). That Court would have

told this one to go back to school.

What is worse, that refresher course would apparently be

insufficient. For it is not just that the majority does not realize

how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care. In

adopting that posture of indifference, the majority does something

novel (though in law, unlike in art, it is rarely a good thing to

be transformative). Before today, we assessed "the purpose and

character" of a copier's use by asking the following question: Does

the work "add[ ] something new, with a further purpose or different

character, altering the [original] with new expression, meaning, or

message"?

Campbell v.

Acuff-Rose Music,

Inc.,

510 U.S.

569, 579 (1994); see

Google, 593 U. S., at ___ (slip

op., at 24). When it did so to a significant degree, we called the

work "transformative" and held that the fair-use test's first

factor favored the copier (though other factors could outweigh that

one). But today's decision-all the majority's protestations

notwithstanding-leaves our first-factor inquiry in shambles. The

majority holds that because Warhol licensed his work to a

magazine-as Goldsmith sometimes also did-the first factor goes

against him. See,

e.g.,

ante, at 35. It does not

matter how different the Warhol is from the original photo-how much

"new expression, meaning, or message" he added. It does not matter

that the silkscreen and the photo do not have the same aesthetic

characteristics and do not convey the same meaning. It does not

matter that because of those dissimilarities, the magazine

publisher did not view the one as a substitute for the other. All

that matters is that Warhol and the publisher entered into a

licensing transaction, similar to one Goldsmith might have done.

Because the artist had such a commercial purpose, all the

creativity in the world could not save him.

That doctrinal shift ill serves copyright's core purpose. The

law does not grant artists (and authors and composers and so on)

exclusive rights-that is, monopolies-for their own sake. It does so

to foster creativity-"[t]o promote the [p]rogress" of both arts and

science. U. S. Const., Art. I, §8, cl. 8. And for that

same reason, the law also protects the fair use of copyrighted

material. Both Congress and the courts have long recognized that an

overly stringent copyright regime actually "stifle[s]" creativity

by preventing artists from building on the work of others.

Stewart v.

Abend,

495 U.S.

207, 236 (1990) (internal quotation marks omitted); see

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 578-579. For, let's be honest,

artists don't create all on their own; they cannot do what they do

without borrowing from or otherwise making use of the work of

others. That is the way artistry of all kinds-visual, musical,

literary-happens (as it is the way knowledge and invention

generally develop). The fair-use test's first factor responds to

that truth: As understood in our precedent, it provides "breathing

space" for artists to use existing materials to make fundamentally

new works, for the public's enjoyment and benefit.

Id., at

579. In now remaking that factor, and thus constricting fair use's

boundaries, the majority hampers creative progress and undermines

creative freedom. I respectfully dissent.[

2]

I

A

Andy Warhol is the avatar of transformative copying. Cf.

Google, 593 U. S., at ___-___ (slip op., at 24-25)

(selecting Warhol, from the universe of creators, to illustrate

what transformative copying is). In his early career, Warhol worked

as a commercial illustrator and became experienced in varied

techniques of reproduction. By night, he used those techniques-in

particular, the silkscreen-to create his own art. His own-even

though in one sense not. The silkscreen enabled him to make

brilliantly novel art out of existing "images carefully selected

from popular culture." D. De Salvo, God Is in the Details, in Andy

Warhol Prints 22 (4th rev. ed. 2003). The works he produced,

connecting traditions of fine art with mass culture, depended on

"appropriation[s]": The use of "elements of an extant image[ ] is

Warhol's entire modus operandi." B. Gopnik, Artistic Appropriation

vs. Copyright Law, N. Y. Times, Apr. 6, 2021, p. C4 (internal

quotation marks omitted). And with that m.o., he changed modern

art; his appropriations and his originality were flipsides of each

other. To a public accustomed to thinking of art as formal works

"belong[ing] in gold frames"-disconnected from the everyday world

of products and personalities-Warhol's paintings landed like a

thunderclap. A. Danto, Andy Warhol 36 (2009). Think Soup Cans or,

in another vein, think Elvis. Warhol had created "something very

new"-"shockingly important, transformative art." B. Gopnik, Warhol

138 (2020); Gopnik, Artistic Appropriation.

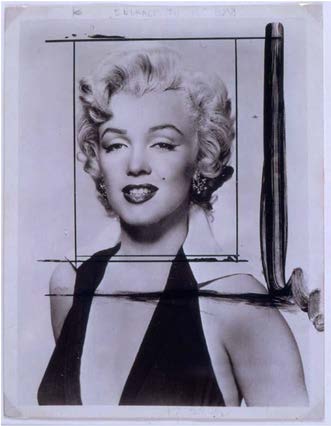

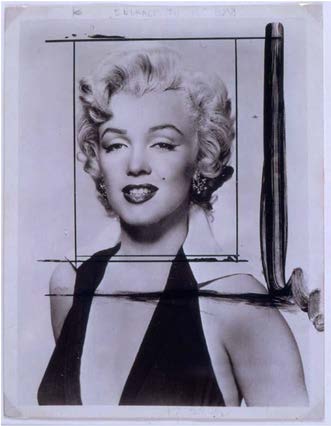

To see the method in action, consider one of Warhol's pre-Prince

celebrity silkscreens-this one, of Marilyn Monroe. He began with a

publicity photograph of the actress. And then he went to work. He

reframed the image, zooming in on Monroe's face to "produc[e] the

disembodied effect of a cinematic close-up." 1 App. 161 (expert

declaration).

At that point, he produced a high-contrast, flattened image on a

sheet of clear acetate. He used that image to trace an outline on

the canvas. And he painted on top-applying exotic colors with "a

flat, even consistency and an industrial appearance."

Id.,

at 165. The same high-contrast image was then reproduced in

negative on a silkscreen, designed to function as a selectively

porous mesh. Warhol would "place the screen face down on the

canvas, pour ink onto the back of the mesh, and use a squeegee to

pull the ink through the weave and onto the canvas."

Id., at

164. On some of his Marilyns (there are many), he reordered the

process-first ink, then color, then (perhaps) ink again. See

id., at 165-166. The result-see for yourself-is miles away

from a literal copy of the publicity photo.

Andy Warhol, Marilyn, 1964, acrylic and silkscreen ink on

linen

And the meaning is different from any the photo had. Of course,

meaning in great art is contestable and contested (as is the

premise that an artwork is great). But note what some experts say

about the complex message(s) Warhol's Marilyns convey. On one

level, those vivid, larger-than-life paintings are celebrity

iconography, making a "secular, profane subject[ ]" "transcendent"

and "eternal."

Id., at 209 (internal quotation marks

omitted). But they also function as a biting critique of the cult

of celebrity, and the role it plays in American life. With

misaligned, "Day-Glo" colors suggesting "artificiality and

industrial production," Warhol portrayed the actress as a "consumer

product." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide 233 (2012); The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marilyn (2023) (online source archived

at https://www.supremecourt.gov). And in so doing, he "exposed the

deficiencies" of a "mass-media culture" in which "such superficial

icons loom so large." 1 App. 208, 210 (internal quotation marks

omitted). Out of a publicity photo came both memorable portraiture

and pointed social commentary.

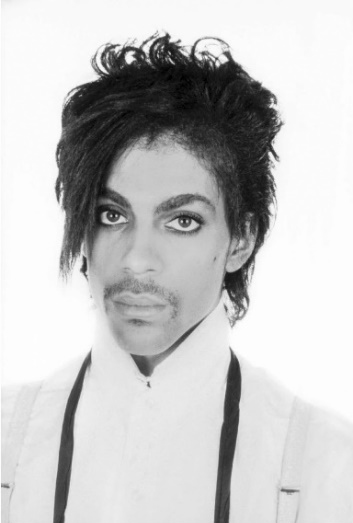

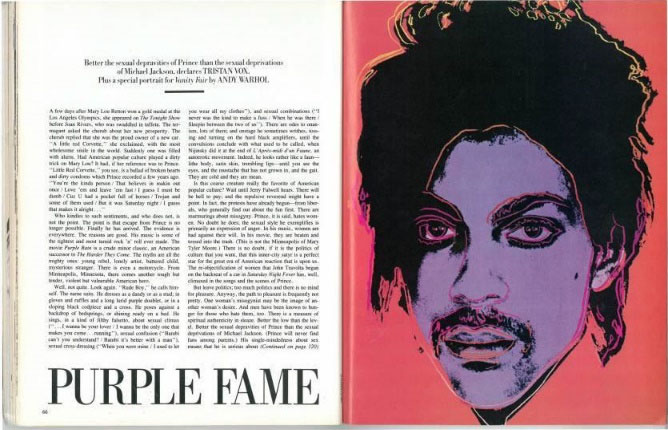

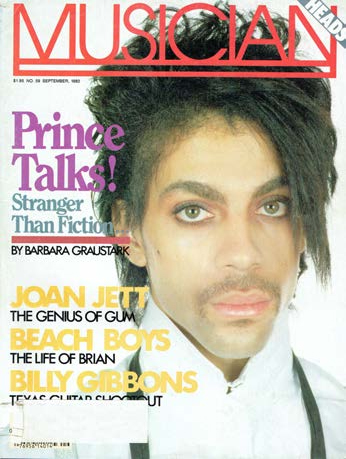

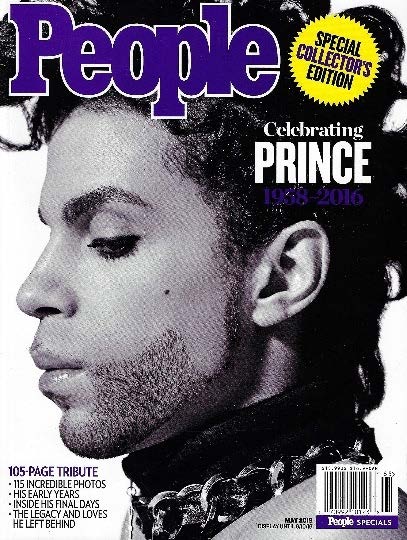

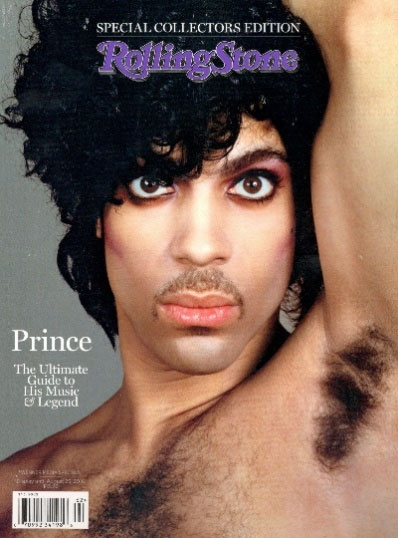

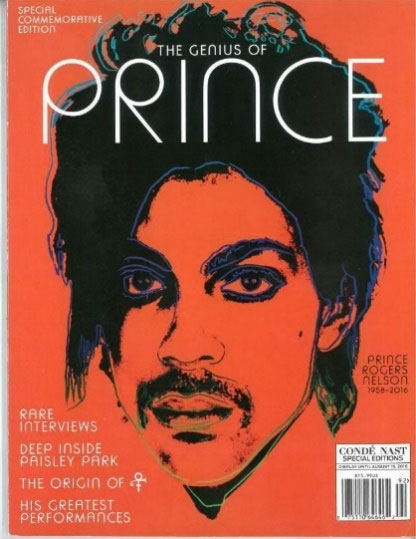

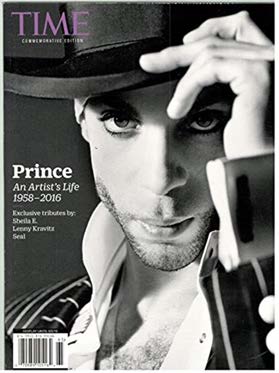

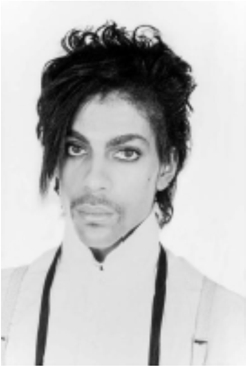

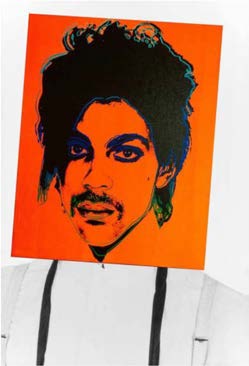

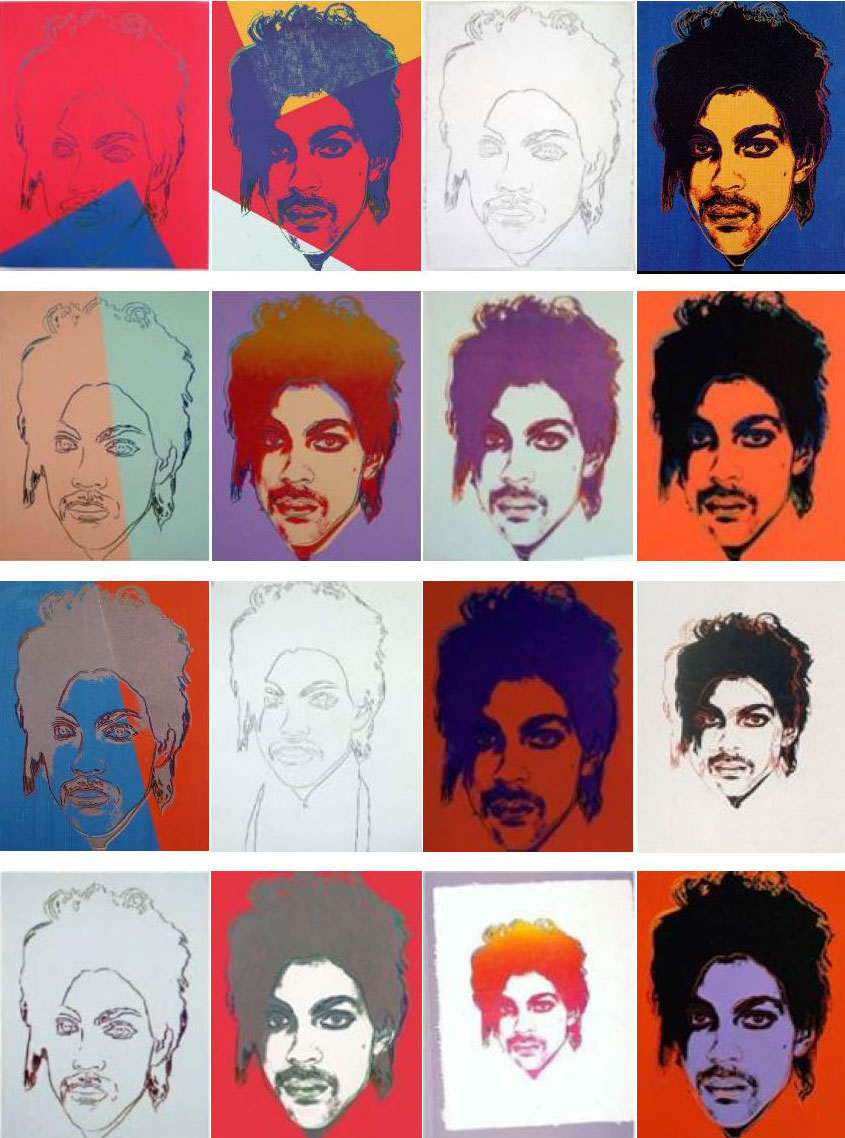

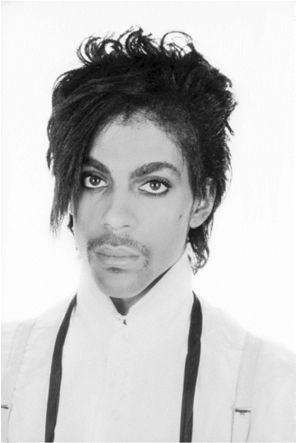

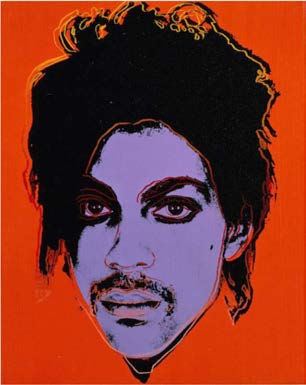

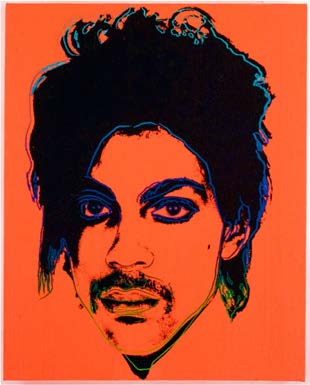

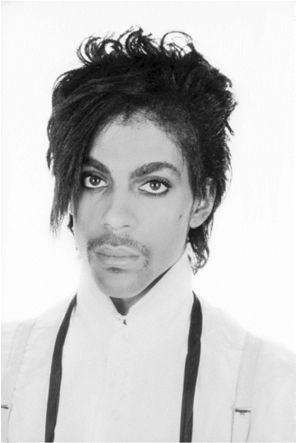

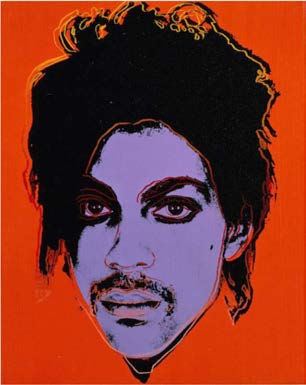

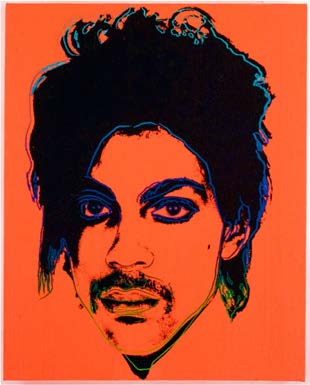

As with Marilyn, similarly with Prince. In 1984, Vanity Fair

commissioned Warhol to create a portrait based on a black-and-white

photograph taken by noted photographer Lynn Goldsmith:

As he did in the Marilyn series, Warhol cropped the photo, so

that Prince's head fills the whole frame: It thus becomes

"disembodied," as if "magically suspended in space."

Id., at

174. And as before, Warhol converted the cropped photo into a

higher-contrast image, incorporated into a silkscreen. That image

isolated and exaggerated the darkest details of Prince's head; it

also reduced his "natural, angled position," presenting him in a

more face-forward way.

Id., at 223. Warhol traced, painted,

and inked, as earlier described. See

supra, at 5-6. He also

made a second silkscreen, based on his tracings; the ink he passed

through that screen left differently colored, out-of-kilter lines

around Prince's face and hair (a bit hard to see in the

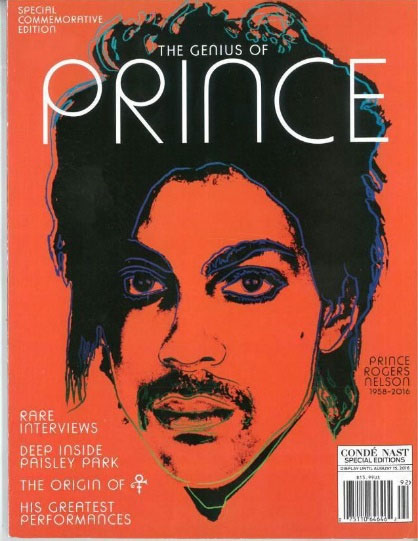

reproduction below-more pronounced in the original). Altogether,

Warhol made 14 prints and two drawings-the Prince series-in a range

of unnatural, lurid hues. See Appendix,

ante, at 39. Vanity

Fair chose the Purple Prince to accompany an article on the

musician. Thirty-two years later, just after Prince died,

Condé Nast paid Warhol (now actually his foundation,

see

supra, at 1, n. 1) to use the Orange Prince on the cover

of a special commemorative magazine. A picture (or two), as the

saying goes, is worth a thousand words, so here is what those

magazines published:

Andy Warhol, Prince, 1984, synthetic paint and silkscreen ink on

canvas

It does not take an art expert to see a transformation-but in

any event, all those offering testimony in this case agreed there

was one. The experts explained, in far greater detail than I have,

the laborious and painstaking work that Warhol put into these and

other portraits. See 1 App. 160-185, 212-216, 222-224. They

described, in ways I have tried to suggest, the resulting visual

differences between the photo and the silkscreen. As one summarized

the matter: The two works are "materially distinct" in "their

composition, presentation, color palette, and media"-

i.e.,

in pretty much all their aesthetic traits.

Id., at

227.[

3] And with the change in form came an

undisputed change in meaning. Goldsmith's focus-seen in what one

expert called the "corporeality and luminosity" of her

depiction-was on Prince's "unique human identity."

Id., at

176, 227. Warhol's focus was more nearly the opposite. His subject

was "not the private person but the public image."

Id., at

159. The artist's "flattened, cropped, exotically colored, and

unnatural depiction of Prince's disembodied head" sought to

"communicate a message about the impact of celebrity" in

contemporary life.

Id., at 227. On Warhol's canvas, Prince

emerged as "spectral, dark, [and] uncanny"-less a real person than

a "mask-like simulacrum."

Id., at 187, 249. He was reframed

as a "larger than life" "icon or totem."

Id., at 257. Yet he

was also reduced: He became the product of a "publicity machine"

that "packages and disseminates commoditized images."

Id.,

at 160. He manifested, in short, the dehumanizing culture of

celebrity in America. The message could not have been more

different.

A thought experiment may pound the point home. Suppose you were

the editor of Vanity Fair or Condé Nast, publishing an

article about Prince. You need, of course, some kind of picture. An

employee comes to you with two options: the Goldsmith photo, the

Warhol portrait. Would you say that you don't really care? That the

employee is free to flip a coin? In the majority's view, you

apparently would. Its opinion, as further discussed below, is built

on the idea that both are just "portraits of Prince" that may

equivalently be "used to depict Prince in magazine stories about

Prince."

Ante, at 12-13; see

ante, at 22-23, and n.

11, 27, n. 15, 33, 35. All I can say is that it's a good thing the

majority isn't in the magazine business. Of course you would care!

You would be drawn aesthetically to one, or instead to the other.

You would want to convey the message of one, or instead of the

other. The point here is not that one is better and the other

worse. The point is that they are fundamentally different. You

would see them not as "substitute[s]," but as divergent ways to (in

the majority's mantra) "illustrate a magazine about Prince with a

portrait of Prince."

Ante, at 15, 33; see

ante, at

22-23, and n. 11, 27, n. 15, 35. Or else you (like the majority)

would not have much of a future in magazine publishing.

In any event, the editors of Vanity Fair and Condé

Nast understood the difference-the gulf in both aesthetics and

meaning-between the Goldsmith photo and the Warhol portrait. They

knew about the photo; but they wanted the portrait. They saw that

as between the two works, Warhol had effected a transformation.

B

The question in this case is whether that transformation should

matter in assessing whether Warhol made "fair use" of Goldsmith's

copyrighted photo. The answer is yes-it should push toward

(although not dictate) a finding of fair use. That answer comports

with the copyright statute, its underlying policy, and our

precedent concerning the two. Under established copyright law

(until today), Warhol's addition of important "new expression,

meaning, [and] message" counts in his favor in the fair-use

inquiry.

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579.

Start by asking a broader question: Why do we have "fair use"

anyway? The majority responds that while copyrights encourage the

making of creative works, fair use promotes their "public

availability."

Ante, at 13 (internal quotation marks

omitted). But that description sells fair use far short. Beyond

promoting "availability," fair use itself advances creativity and

artistic progress. See

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 575, 579

(fair use is "necessary to fulfill copyright's very purpose"-to

"promote science and the arts"). That is because creative work does

not happen in a vacuum. "Nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever

could," said songwriter Richard Rodgers, maybe thinking not only

about love and marriage but also about how the Great American

Songbook arose from vaudeville, ragtime, the blues, and

jazz.[

4] This Court has long understood the

point-has gotten how new art, new invention, and new knowledge

arise from existing works. Our seminal opinion on fair use quoted

the illustrious Justice Story:

"In truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and

can be, few, if any, things, which . . . are strictly new and

original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art,

borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well

known and used before."

Id., at 575 (quoting

Emerson

v.

Davies, 8 F. Cas. 615, 619 (No. 4,436) (CC Mass.

1845)).

Because that is so, a copyright regime with no escape valves

would "stifle the very creativity which [the] law is designed to

foster."

Stewart, 495 U. S., at 236. Fair use is such an

escape valve. It "allow[s] others to build upon" copyrighted

material, so as not to "put manacles upon" creative progress.

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 575 (internal quotation marks

omitted). In short, copyright's core value-promoting

creativity-sometimes demands a pass for copying.

To identify when that is so, the courts developed and Congress

later codified a multi-factored inquiry. As the majority describes,

see

ante, at 14, the current statute sets out four

non-exclusive considerations to guide courts. They are: (1) "the

purpose and character of the use" made of the copyrighted work,

"including whether such use is of a commercial nature"; (2) "the

nature of the copyrighted work"; (3) "the amount and substantiality

of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a

whole"; and (4) "the effect of the use upon the potential market

for or value of the copyrighted work."17 U. S. C. §107.

Those factors sometimes point in different directions; if so, a

court must weigh them against each other. In doing so, we have

stated, courts should view the fourth factor-which focuses on the

copyright holder's economic interests-as the "most important." See

Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v.

Nation

Enterprises,

471 U.S.

539, 566 (1985).[

5] But the overall balance

cannot come out right unless each factor is assessed correctly.

This case, of course, is about (and only about) the first.

And that factor is distinctive: It is the only one that focuses

on what the copier's use of the original work accomplishes. The

first factor asks about the "character" of that use-its "main or

essential nature[,] esp[ecially] as strongly marked and serving to

distinguish." Webster's Third New International Dictionary 376

(1976). And the first factor asks about the "purpose" of the

use-the "object, effect, or result aimed at, intended, or

attained."

Id., at 1847. In that way, the first factor gives

the copier a chance to make his case. See P. Leval, Toward a Fair

Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105, 1116 (1990) (describing

factor 1 as "the soul of " the "fair use defense"). Look, the

copier can say, at how I altered the original, and what I achieved

in so doing. Look at how (as Judge Leval's seminal article put the

point) the original was "used as raw material" and was "transformed

in the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights."

Id., at 1111. That is hardly the end of the fair-use inquiry

(commercialism, too, may bear on the first factor, and anyway there

are three factors to go), but it matters profoundly. Because when a

transformation of the original work has occurred, the user of the

work has made the kind of creative contribution that copyright law

has as its object.

Don't take it from me (or Judge Leval): The above is exactly

what this Court has held about how to apply factor 1. In

Campbell, our primary case on the topic, we stated that the

first factor's purpose-and-character test "central[ly]" concerns

"whether and to what extent the new work is 'transformative.' " 510

U. S., at 579 (quoting Leval 1111). That makes sense, we explained,

because "the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is

generally furthered by the creation of transformative works." 510

U. S., at 579. We then expounded on when such a transformation

happens. Harking back to Justice Story, we explained that a "new

work" might "merely 'supersede[ ] the objects' of the original

creation"-meaning, that it does no more, and for no other end, than

the first work had.

Ibid. (quoting

Folsom v.

Marsh,

9 F. Cas. 342, 348 (No. 4,901) (CC Mass. 1841)). But

alternatively, the new work could "add[ ] something new, with a

further purpose or different character, altering the first with new

expression, meaning, or message." 510 U. S., at 579. Forgive me,

but given the majority's stance (see,

e.g.,

ante, at

33), that bears repeating: The critical factor 1 inquiry, we held,

is whether a new work alters the first with "new expression,

meaning, or message." The more it does so, the more transformative

the new work. And (here is the final takeaway) "the more

transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of

other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding

of fair use." 510 U. S., at 579. Under that approach, the

Campbell Court held, the rap group 2 Live Crew's

"transformative" copying of Roy Orbison's "Pretty Woman" counted in

favor of fair use.

Id., at 583. And that was so even though

the rap song was, as everyone agreed, recorded and later sold for

profit. See

id., at 573.

Just two Terms ago, in

Google, we made all the same

points. We quoted

Campbell in explaining that the factor 1

inquiry is "whether the copier's use 'adds something new, with a

further purpose or different character, altering' the copyrighted

work 'with new expression, meaning, or message.' " 593 U. S., at

___ (slip op., at 24). We again described "a copying use that adds

something new and important" as "transformative."

Ibid. We

reiterated that protecting transformative uses "stimulate[s]

creativity" and thus "fulfill[s] the objective of copyright law."

Ibid. (quoting Leval 1111). And then we gave an example.

Yes, of course, we pointed to Andy Warhol. (The majority claims not

to be embarrassed by this embarrassing fact because the specific

reference was to his Soup Cans, rather than his celebrity images.

But drawing a distinction between a "commentary on

consumerism"-which is how the majority describes his soup canvases,

ante, at 27-and a commentary on celebrity culture,

i.e., the turning of people into consumption items, is

slicing the baloney pretty thin.) Finally, the Court conducted the

first-factor inquiry it had described. Google had replicated Sun

Microsystems' computer code as part of a "commercial endeavor,"

done "for commercial profit." 593 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 27).

No matter, said the Court. "[M]any common fair uses are

indisputably commercial."

Ibid. What mattered instead was

that Google had used Sun's code to make "something new and

important": a "highly creative and innovative" software platform.

Id., at ___-___ (slip op., at 24-25). The use of the code,

the Court held, was therefore "transformative" and "point[ed]

toward fair use."

Id., at ___, ___ (slip op., at 25,

28).

Campbell and

Google also illustrate the difference

it can make in the world to protect transformative works through

fair use. Easy enough to say (as the majority does, see

ante, at 36) that a follow-on creator should just pay a

licensing fee for its use of an original work. But sometimes

copyright holders charge an out-of-range price for licenses. And

other times they just say no. In

Campbell, for example,

Orbison's successor-in-interest turned down 2 Live Crew's request

for a license, hoping to block the rap take-off of the original

song. See 510 U. S., at 572-573. And in

Google, the parties

could not agree on licensing terms, as Sun insisted on conditions

that Google thought would have subverted its business model. See

593 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 3). So without fair use, 2 Live

Crew's and Google's works-however new and important-might never

have been made or, if made, never have reached the public. The

prospect of that loss to "creative progress" is what lay behind the

Court's inquiry into transformativeness-into the expressive novelty

of the follow-on work (regardless whether the original creator

granted permission).

Id., at ___ (slip op., at 25); see

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579.

Now recall all the ways Warhol, in making a Prince portrait from

the Goldsmith photo, "add[ed] something new, with a further purpose

or different character"-all the ways he "alter[ed] the [original

work's] expression, meaning, [and] message."

Ibid. The

differences in form and appearance, relating to "composition,

presentation, color palette, and media." 1 App. 227; see

supra, at 7-10. The differences in meaning that arose from

replacing a realistic-and indeed humanistic-depiction of the

performer with an unnatural, disembodied, masklike one. See

ibid. The conveyance of new messages about celebrity culture

and its personal and societal impacts. See

ibid. The

presence of, in a word, "transformation"-the kind of creative

building that copyright exists to encourage. Warhol's use, to be

sure, had a commercial aspect. Like most artists, Warhol did not

want to hide his works in a garret; he wanted to sell them. But as

Campbell and

Google both demonstrate (and as further

discussed below), that fact is nothing near the showstopper the

majority claims. Remember, the more transformative the work, the

less commercialism matters. See

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579;

supra, at 14;

ante, at 18 (acknowledging the point,

even while refusing to give it any meaning). The dazzling

creativity evident in the Prince portrait might not get Warhol all

the way home in the fair-use inquiry; there remain other factors to

be considered and possibly weighed against the first one. See

supra, at 2, 10, 14. But the "purpose and character of

[Warhol's] use" of the copyrighted work-what he did to the

Goldsmith photo, in service of what objects-counts powerfully in

his favor. He started with an old photo, but he created a new new

thing.[

6]

II

The majority does not see it. And I mean that literally. There

is precious little evidence in today's opinion that the majority

has actually looked at these images, much less that it has engaged

with expert views of their aesthetics and meaning. Whatever new

expression Warhol added, the majority says, was not transformative.

See

ante, at 25. Apparently, Warhol made only "modest

alterations."

Ante, at 33. Anyone, the majority suggests,

could have "crop[ped], flatten[ed], trace[d], and color[ed] the

photo" as Warhol did.

Ante, at 8. True, Warhol portrayed

Prince "somewhat differently."

Ante, at 33. But the "degree

of difference" is too small: It consists merely in applying

Warhol's "characteristic style"-an aesthetic gloss, if you will-"to

bring out a particular meaning" that was already "available in

[Goldsmith's] photograph."

Ibid. So too, Warhol's commentary

on celebrity culture matters not at all; the majority is not

willing to concede that it even exists. See

ante, at 34

("even if such commentary is perceptible"). And as for the District

Court's view that Warhol transformed Prince from a "vulnerable,

uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure," the

majority is downright dismissive.

Ante, at 32. Vulnerable,

iconic-who cares? The silkscreen and the photo, the majority

claims, still have the same "essential nature."

Ante, at 25,

n. 14 (emphasis deleted).

The description is disheartening. It's as though Warhol is an

Instagram filter, and a simple one at that (

e.g.,

sepia-tinting). "What is all the fuss about?," the majority wants

to know. Ignoring reams of expert evidence-explaining, as every art

historian could explain, exactly what the fuss is about-the

majority plants itself firmly in the "I could paint that" school of

art criticism. No wonder the majority sees the two images as

essentially fungible products in the magazine market-publish this

one, publish that one, what does it matter? See

ante, at

22-23;

supra, at 10. The problem is that it

does

matter, for all the reasons given in the record and discussed

above. See

supra, at 9-10. Warhol based his silkscreen on a

photo, but fundamentally changed its character and meaning. In

belittling those creative contributions, the majority guarantees

that it will reach the wrong result.

Worse still, the majority maintains that those contributions,

even if significant, just would not matter. All of Warhol's

artistry and social commentary is negated by one thing: Warhol

licensed his portrait to a magazine, and Goldsmith sometimes

licensed her photos to magazines too. That is the sum and substance

of the majority opinion. Over and over, the majority incants that

"[b]oth [works] are portraits of Prince used in magazines to

illustrate stories about Prince"; they therefore both "share

substantially the same purpose"-meaning, a commercial one.

Ante, at 22-23, 38; see

ante, at 12-13, 27, n. 15,

33, 35. Or said otherwise, because Warhol entered into a licensing

transaction with Condé Nast, he could not get any help

from factor 1-regardless how transformative his image was. See,

e.g.,

ante, at 35 (Warhol's licensing "outweigh[s]"

any "new meaning or message" he could have offered). The majority's

commercialism-trumps-creativity analysis has only one way out. If

Warhol had used Goldsmith's photo to comment on or critique

Goldsmith's photo, he might have availed himself of that

factor's benefit (though why anyone would be interested in that

work is mysterious). See

ante, at 34. But because he instead

commented on

society-the dehumanizing culture of

celebrity-he is (go figure) out of luck.

From top-to-bottom, the analysis fails. It does not fit the

copyright statute. It is not faithful to our precedent. And it does

not serve the purpose both Congress and the Court have understood

to lie at the core of fair use: "stimulat[ing] creativity," by

enabling artists and writers of every description to build on prior

works.

Google, 593 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 24). That is

how art, literature, and music happen; it is also how all forms of

knowledge advance. Even as the majority misconstrues the law, it

misunderstands-and threatens-the creative process.

Start with what the statute tells us about whether the factor 1

inquiry should disregard Warhol's creative contributions because he

licensed his work. (Sneak preview: It shouldn't.) The majority

claims the text as its strong suit, viewing our precedents' inquiry

into new expression and meaning as a faulty "paraphrase" of the

statutory language.

Ante, at 28-30. But it is the majority,

not

Campbell and

Google, that misreads

§107(1). First, the key term "character" plays little

role in the majority's analysis. See

ante, at 12-13, 22-23,

and n. 11, 29 (statements of central test or holding referring only

to "purpose"). And you can see why, given the counter-intuitive

meaning the majority (every so often) provides. See

ante, at

24-25, and n. 14. When referring to the "character" of what Warhol

did, the majority says merely that he "licensed Orange Prince to

Condé Nast for $10,000." See

ante, at 24. But

that reductionist view rids the term of most of its ordinary

meaning. "Character" typically refers to a thing's "main or

essential nature[,] esp[ecially] as strongly marked and serving to

distinguish." Webster's Third 376; see

supra, at 13. The

essential and distinctive nature of an artist's use of a work

commonly involves artistry-as it did here. See also

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 582, 588-589 (discussing the

expressive "character" of 2 Live Crew's rap). So the term

"character" makes significant everything the record contains-and

everything everyone (save the majority) knows-about the differences

in expression and meaning between Goldsmith's photo and Warhol's

silkscreen.

Second, the majority significantly narrows §107(1)'s

reference to "purpose" (thereby paralleling its constriction of

"character"). It might be obvious to you that artists have artistic

purposes. And surely it was obvious to the drafters of a law aiming

to promote artistic (and other kinds of ) creativity. But not to

the majority, which again cares only about Warhol's decision to

license his art. Warhol's purpose, the majority says, was just to

"depict Prince in [a] magazine stor[y] about Prince" in exchange

for money.

Ante, at 12-13. The majority spurns all that

mattered to the artist-evident on the face of his work-about

"expression, meaning, [and] message."

Campbell, 510 U. S.,

at 579;

Google, 593 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 24). That

indifference to purposes beyond the commercial-for what an artist,

most fundamentally, wants to communicate-finds no support in

§107(1).[

7]

Still more, the majority's

commercialism-über-alles view of the factor 1

inquiry fits badly with two other parts of the fair-use provision.

To begin, take the preamble, which gives examples of uses often

thought fair: "criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching[,] . .

. scholarship, or research." §107. As we have

explained, an emphasis on commercialism would "swallow" those

uses-that is, would mostly

deprive them of fair-use

protection.

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 584. For the listed

"activities are generally conducted for profit in this country."

Ibid. (internal quotation marks omitted). "No man but a

blockhead," Samuel Johnson once noted, "ever wrote[ ] except for

money." 3 Boswell's Life of Johnson 19 (G. Hill ed. 1934). And

Congress of course knew that when it drafted the preamble.

Next, skip to the last factor in the fair-use test: "the effect

of the use upon the potential market for or value of the

copyrighted work." §107(4). You might think that when

Congress lists two different factors for consideration, it is

because the two factors are, well, different. But the majority

transplants factor 4 into factor 1. Recall that the majority

conducts a kind of market analysis: Warhol, the majority says,

licensed his portrait of Prince to a magazine that Goldsmith could

have licensed her photo to-and so may have caused her economic

harm. See

ante, at 22-23; see also

ante, at 19

(focusing on whether a follow-on work is a market "substitute" for

the original);

ante, at 4 (Gorsuch, J., concurring)

(describing the "salient point" as whether Warhol's "use involved

competition with Ms. Goldsmith's image"). That issue is no doubt

important in the fair-use inquiry. But it is the stuff of factor 4:

how Warhol's use affected the "value of " or "market for"

Goldsmith's photo. Factor 1 focuses on the other side of the

equation: the new expression, meaning, or message that may come

from someone else using the original. Under the statute, courts are

supposed to strike a balance between the two-and thus between

rewarding original creators and enabling others to build on their

works. That cannot happen when a court, Ã la the

majority, double-counts the first goal and ignores the second.

Is it possible I overstate the matter? I would like for that to

be true. And a puzzling aspect of today's opinion is that it

occasionally acknowledges the balance that the fair-use provision

contemplates. So, for example, the majority notes after reviewing

the relevant text that "the central question [the first factor]

asks" is whether the new work "adds something new" to the

copyrighted one.

Ante, at 15 (internal quotation marks

omitted). Yes, exactly. And in other places, the majority suggests

that a court should consider in the factor 1 analysis not merely

the commercial context but also the copier's addition of "new

expression," including new meaning or message.

Ante, at 12;

see

ante, at 18, 24-25, n. 13, 25, 32. In that way, the

majority opinion differs from Justice Gorsuch's concurrence, which

would exclude all inquiry into whether a follow-on work is

transformative. See

ante, at 2, 4. And it is possible lower

courts will pick up on that difference, and ensure that the

"newness" of a follow-on work will continue to play a significant

role in the factor 1 analysis. If so, I'll be happy to discover

that my "claims [have] not age[d] well."

Ante, at 36. But

that would require courts to do what the majority does not: make a

serious inquiry into the follow-on artist's creative contributions.

The majority's refusal to do so is what creates the oddity at the

heart of today's opinion. If "newness" matters (as the opinion

sometimes says), then why does the majority dismiss all the newness

Warhol added just because he licensed his portrait to

Condé Nast? And why does the majority insist more

generally that in a commercial context "convey[ing] a new meaning

or message" is "not enough for the first factor to favor fair use"?

Ante, at 35.

Certainly not because of our precedent-which conflicts with

nearly all the majority says. As explained earlier, this Court has

decided two important cases about factor 1. See

supra, at

14-16. In each, the copier had built on the original to make a

product for sale-so the use was patently commercial. And in each,

that fact made no difference, because the use was also

transformative. The copier, we held, had made a significant

creative contribution-had added real value. So in

Campbell,

we did not ask whether 2 Live Crew and Roy Orbison both meant to

make money by "including a catchy song about women on a record

album." But cf.

ante, at 12-13 (asking whether Warhol and

Goldsmith both meant to charge for "depict[ing] Prince in magazine

stories about Prince"). We instead asked whether 2 Live Crew had

added significant "new expression, meaning, [and] message"; and

because we answered yes, we held that the group's rap song did not

"merely supersede the objects of the original creation." 510 U. S.,

at 579 (internal quotation marks and alteration omitted).

Similarly, in

Google, we took for granted that Google (the

copier) and Sun (the original author) both meant to market software

platforms facilitating the same tasks-just as (in the majority's

refrain) Warhol and Goldsmith both wanted to market images

depicting the same subject. See 593 U. S., at ___, ___ (slip op.,

at 25, 27). "So what?" was our basic response. Google's copying had

enabled the company to make a "highly creative and innovative

tool," advancing "creative progress" and thus serving "the basic

constitutional objective of copyright."

Id., at ___ (slip

op., at 25) (internal quotation marks omitted). Search today's

opinion high and low, you will see no such awareness of how copying

can help produce valuable new works.

Nor does our precedent support the majority's strong distinction

between follow-on works that "target" the original and those that

do not.

Ante, at 35. (Even the majority does not claim that

anything in the text does so.) True enough that the rap song in

Campbell fell into the former category: 2 Live Crew urged

that its work was a parody of Orbison's song. But even in

discussing the value of parody,

Campbell made clear the

limits of targeting's importance. The Court observed that as the

"extent of transformation" increases, the relevance of targeting

decreases. 510 U. S., at 581, n. 14.

Google proves the

point. The new work there did not parody, comment on, or otherwise

direct itself to the old: The former just made use of the latter

for its own devices. Yet that fact never made an appearance in the

Court's opinion; what mattered instead was the "highly creative"

use Google had made of the copied code. That decision is on point

here. Would Warhol's work really have been more worthy of

protection if it had (somehow) "she[d] light" on Goldsmith's

photograph, rather than on Prince, his celebrity status, and

celebrity culture?

Ante, at 27. Would that Goldsmith-focused

work (whatever it might be) have more meaningfully advanced

creative progress, which is copyright's raison d'être,

than the work he actually made? I can't see how; more like the

opposite. The majority's preference for the directed work,

apparently on grounds of necessity, see

ante, at 27, 34-35,

again reflects its undervaluing of transformative copying as a core

part of artistry.

And there's the rub. (Yes, that's mostly Shakespeare.) As

Congress knew, and as this Court once saw, new creations come from

building on-and, in the process, transforming-those coming before.

Today's decision stymies and suppresses that process, in art and

every other kind of creative endeavor. The decision enhances a

copyright holder's power to inhibit artistic development, by

enabling her to block even the use of a work to fashion something

quite different. Or viewed the other way round, the decision

impedes non-copyright holders' artistic pursuits, by preventing

them from making even the most novel uses of existing materials. On

either account, the public loses: The decision operates to

constrain creative expression.[

8]

The effect, moreover, will be dramatic. Return again to Justice

Story, see

supra, at 11-12: "[I]n literature, in science and

in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things" that are "new

and original throughout."

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 575

(quoting

Emerson, 8 F. Cas., at 619). Every work "borrows,

and must necessarily" do so. 510 U. S., at 575. Creators themselves

know that fact deep in their bones. Here is Mark Twain on the

subject: "The kern[e]l, the soul-let us go further and say the

substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material" of creative

works-all are "consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million

outside sources." Letter from M. Twain to H. Keller, in 2 Mark

Twain's Letters 731 (1917); see also

id., at 732 (quoting

Oliver Wendell Holmes-no, not that one, his father the poet-as

saying "I have never originated anything altogether myself, nor met

anybody who had"). "[A]ppropriation, mimicry, quotation, allusion

and sublimated collaboration," novelist Jonathan Lethem has

explained, are "a kind of sine qua non of the creative act, cutting

across all forms and genres in the realm of cultural production."

The Ecstasy of Influence, in Harper's Magazine 61 (Feb. 2007). Or

as Mary Shelley once wrote, there is no such thing as "creating out

of [a] void." Frankenstein ix (1831).[

9]

Consider, in light of those authorial references, how the

majority's factor 1 analysis might play out in literature. And why

not start with the best? Shakespeare borrowed over and over and

over. See,

e.g., 8 Narrative and Dramatic Sources of

Shakespeare 351-352 (G. Bullough ed. 1975) ("Shakespeare was an

adapter of other men's tales and plays; he liked to build a new

construction on something given"). I could point to a whole slew of

works, but let's take Romeo and Juliet as an example. Shakespeare's

version copied most directly from Arthur Brooke's The Tragical

History of Romeus and Juliet, written a few decades earlier (though

of course Brooke copied from someone, and that person copied from

someone, and that person . . . going back

at least to Ovid's

story about Pyramus and Thisbe). Shakespeare took plot, characters,

themes, even passages: The friar's line to Romeo, "Art thou a man?

Thy form cries out thou art," appeared in Brooke as "Art thou a

man? The shape saith so thou art." Bullough 387. (Shakespeare was,

among other things, a good editor.) Of course Shakespeare also

added loads of genius, and so made the borrowed stories "uniquely

Shakespearian." G. Williams, Shakespeare's Basic Plot Situation, 2

Shakespeare Quarterly No. 4, p. 313 (Oct. 1951). But on the

majority's analysis? The two works-Shakespeare's and Brooke's-are

just two stories of star-crossed lovers written for commercial

gain. Shakespeare would not qualify for fair use; he would not even

come out ahead on factor 1.

And if you think that's just Shakespeare, here are a couple

more. (Once you start looking, examples are everywhere.) Lolita,

though hard to read today, is usually thought one of the greatest

novels of the 20th century. But the plotline-an adult man takes a

room as a lodger; embarks on an obsessive sexual relationship with

the preteen daughter of the house; and eventually survives her

death, remaining marked forever-appears in a story by Heinz von

Lichberg written a few decades earlier. Oh, and the girl's name is

Lolita in both versions. See generally M. Maar, The Two Lolitas

(2005). All that said, the two works have little in common

artistically; nothing literary critics admire in the second Lolita

is found in the first. But to the majority? Just two stories of

revoltingly lecherous men, published for profit. So even factor 1

of the fair-use inquiry would not aid Nabokov. Or take one of the

most famed adventure stories ever told. Here is the provenance of

Treasure Island, as Robert Louis Stevenson himself described

it:

"No doubt the parrot once belonged to Robinson Crusoe. No doubt

the skeleton is conveyed from [Edgar Allan] Poe. I think little of

these, they are trifles and details; and no man can hope to have a

monopoly of skeletons or make a corner in talking birds. . . . It

is my debt to Washington Irving that exercises my conscience, and

justly so, for I believe plagiarism was rarely carried farther. . .

. Billy Bones, his chest, the company in the parlor, the whole

inner spirit and a good deal of the material detail of my first

chapters-all were there, all were the property of Washington

Irving." My First Book-

Treasure Island, in 21 Syracuse

University Library Associates Courier No. 2, p. 84 (1986).

Odd that a book about pirates should have practiced piracy? Not

really, because tons of books do-and not many in order to "target"

or otherwise comment on the originals. "Thomas Mann, himself a

master of [the art,] called [it] 'higher cribbing.' " Lethem 59.

The point here is that most writers worth their salt steal other

writers' moves-and put them to other, often better uses. But the

majority would say, again and yet again in the face of such

transformative copying, "no factor 1 help and surely no fair

use."

Or how about music? Positively rife with copying of all kinds.

Suppose some early blues artist (W. C. Handy, perhaps?) had

copyrighted the 12-bar, three-chord form-the essential foundation

(much as Goldsmith's photo is to Warhol's silkscreen) of many blues

songs. Under the majority's view, Handy could then have

controlled-meaning, curtailed-the development of the genre. And

also of a fair bit of rock and roll. "Just another rendition of

12-bar blues for sale in record stores," the majority would say to

Chuck Berry (Johnny B. Goode), Bill Haley (Rock Around the Clock),

Jimi Hendrix (Red House), or Eric Clapton (Crossroads). Or to

switch genres, imagine a pioneering classical composer (Haydn?) had

copyrighted the three-section sonata form. "One more piece built on

the same old structure, for use in concert halls," the majority

might say to Mozart and Beethoven and countless others: "Sure, some

new notes, but the backbone of your compositions is identical."

And then, there's the appropriation of those notes, and

accompanying words, for use in new and different ways. Stravinsky

reportedly said that great composers do not imitate, but instead

steal. See P. Yates, Twentieth Century Music 41 (1967). At any

rate, he would have known. He took music from all over-from Russian

folk melodies to Schoenberg-and made it inimitably his own. And

then-as these things go-his music became a source for others.

Charlie Parker turned The Rite of Spring into something of a jazz

standard: You can still hear the Stravinsky lurking, but jazz

musicians make the composition a thing of a different kind. And

popular music? I won't point fingers, but maybe rock's only Nobel

Laureate and greatest-ever lyricist is known for some

appropriations? See M. Gilmore, The Rolling Stone Interview,

Rolling Stone, Sept. 27, 2012, pp. 51, 81.[

10]

He wouldn't be alone. Here's what songwriter Nick Cave (he of the

Bad Seeds) once said about how music develops:

"The great beauty of contemporary music, and what gives it its

edge and vitality, is its devil-may-care attitude toward

appropriation-everybody is grabbing stuff from everybody else,

all the time. It's a feeding frenzy of borrowed ideas that

goes toward the advancement of rock music-the great artistic

experiment of our era." The Red Hand Files (Apr. 2020) (online

source archived at https://www.supremecourt.gov).

But not as the majority sees the matter. Are these guys making

money? Are they appropriating for some different reason than to

critique the thing being borrowed? Then they're "shar[ing] the

objectives" of the original work, and will get no benefit from

factor 1, let alone protection from the whole fair-use test.

Ante, at 24.

Finally, back to the visual arts, for while Warhol may have been

the master appropriator within that field, he had plenty of

company; indeed, he worked within an established tradition going

back centuries (millennia?). The representatives of three giants of

modern art (you may know one for his use of comics) describe the

tradition as follows: "[T]he use and reuse of existing imagery" are

"part of art's lifeblood"-"not just in workaday practice or

fledgling student efforts, but also in the revolutionary moments of

art history." Brief for Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, and

Joan Mitchell Foundations et al. as

Amici Curiae 6.

Consider as one example the reclining nude. Probably the first

such figure in Renaissance art was Giorgione's Sleeping Venus.

(Note, though, in keeping with the "nothing comes from nothing"

theme, that Giorgione apparently modeled his canvas on a woodcut

illustration by Francesco Colonna.) Here is Giorgione's

painting:

Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510, oil on canvas

But things were destined not to end there. One of Giorgione's

pupils was Titian, and the former student undertook to riff on his

master. The resulting Venus of Urbino is a prototypical example of

Renaissance

imitatio-the creation of an original work from

an existing model. See

id., at 8; 1 G. Vasari, Lives of the

Artists 31, 444 (G. Bull transl. 1965). You can see the

resemblance-but also the difference:

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas

The majority would presumably describe these Renaissance

canvases as just "two portraits of reclining nudes painted to sell

to patrons." Cf.

ante, at 12-13, 22-23. But wouldn't that

miss something-indeed, everything-about how an artist engaged with

a prior work to create new expression and add new value?

And the reuse of past images was far from done. For here is

Édouard Manet's Olympia, now considered a

foundational work of artistic modernism, but referring in obvious

ways to Titian's (and back a step, to Giorgione's) Venus:

Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas

Here again consider the account of the Rauschenberg,

Lichtenstein, and Mitchell Foundations: "The revolutionary shock of

the painting depends on how traditional imagery remains the

painting's recognizable foundation, even as that imagery is

transformed and wrenched into the present." Brief as

Amici

Curiae 9. It is an especially striking example of a recurrent

phenomenon-of how the development of visual art works across time

and place, constantly building on what came earlier. In fact, the

Manet has itself spawned further transformative paintings, from

Cézanne to a raft of contemporary artists across the

globe. See

id., at 10-11. But the majority, as to these

matters, is uninterested and unconcerned.

Take a look at one last example, from a modern master very

different from Warhol, but availing himself of the same

appropriative traditions. On the left (below) is

Velázquez's portrait of Pope Innocent X; on the right

is Francis Bacon's Study After Velázquez's

Portrait.

Velázquez, Pope

Innocent X,c. 1650, oil on canvas

Francis Bacon, Study After

Velazquez's Portrait of PopeInnocent X, 1953, oil on canvas

To begin with, note the word "after"

in Bacon's title. Copying is so deeply rooted in the visual arts

that there is a naming convention for it, with "after" denoting

that a painting is some kind of "imitation of a known work." M.

Clarke, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms 5 (2d ed. 2010).

Bacon made frequent use of that convention. He was especially taken

by Velázquez's portrait of Innocent X, referring to

it in tens of paintings. In the one shown above, Bacon retained the

subject, scale, and composition of the Velázquez

original. Look at one, look at the other, and you know Bacon

copied. But he also transformed. He invested his portrait with new

"expression, meaning, [and] message," converting

Velázquez's study of magisterial power into one of

mortal dread.

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579.

But the majority, from all it says, would find the change

immaterial. Both paintings, after all, are "portraits of [Pope

Innocent X] used to depict [Pope Innocent X]" for hanging in some

interior space,

ante, at 12-13; so on the majority's

reasoning, someone in the market for a papal portrait could use

either one, see

ante, at 22-23. Velázquez's

portrait, although Bacon's model, is not "the object of [his]

commentary."

Ante, at 27; see A. Zweite, Bacon's Scream, in

Francis Bacon: The Violence of the Real 71 (A. Zweite ed. 2006)

(Bacon "was not seeking to expose Velázquez's

masterpiece," but instead to "adapt it" and "give it a new

meaning"). And absent that "target[ing]," the majority thinks the

portraits' distinct messages make no difference.

Ante, at

27. Recall how the majority deems irrelevant the District Court's

view that the Goldsmith Prince is vulnerable, the Warhol Prince

iconic. Too small a "degree of difference," according to the

majority.

Ante, at 33-34; see

supra, at 17. So too

here, presumably: the stolid Pope, the disturbed Pope-it just

doesn't matter. But that once again misses what a copier

accomplished: the making of a wholly new piece of art from an

existing one.

The majority thus treats creativity as a trifling part of the

fair-use inquiry, in disregard of settled copyright principles and

what they reflect about the artistic process. On the majority's

view, an artist had best not attempt to market even a

transformative follow-on work-one that adds significant new

expression, meaning, or message. That added value (unless it comes

from critiquing the original) will no longer receive credit under

factor 1. And so it can never hope to outweigh factor 4's

assessment of the copyright holder's interests. The result will be

what this Court has often warned against: suppression of "the very

creativity which [copyright] law is designed to foster."

Stewart, 495 U. S., at 236; see

supra, at 11-12. And

not just on the margins. Creative progress unfolds through use and

reuse, framing and reframing: One work builds on what has gone

before; and later works build on that one; and so on through time.

Congress grasped the idea when it directed courts to attend to the

"purpose and character" of artistic borrowing-to what the borrower

has made out of existing materials. That inquiry recognizes the

value in using existing materials to fashion something new. And so

too, this Court-from Justice Story's time to two Terms ago-has

known that it is through such iterative processes that knowledge

accumulates and art flourishes. But not anymore. The majority's

decision is no "continuation" of "existing copyright law."

Ante, at 37. In declining to acknowledge the importance of

transformative copying, the Court today, and for the first time,

turns its back on how creativity works.

III

And the workings of creativity bring us back to Andy Warhol. For

Warhol, as this Court noted in

Google, is the very

embodiment of transformative copying. He is proof of concept-that

an artist working from a model can create important new expression.

Or said more strongly, that appropriations can help bring great art

into being. Warhol is a towering figure in modern art not despite

but because of his use of source materials. His work-whether Soup

Cans and Brillo Boxes or Marilyn and Prince-turned something not

his into something all his own. Except that it also became all of

ours, because his work today occupies a significant place not only

in our museums but in our wider artistic culture. And if the

majority somehow cannot see it-well, that's what evidentiary

records are for. The one in this case contained undisputed

testimony, and lots of it, that Warhol's Prince series conveyed a

fundamentally different idea, in a fundamentally different artistic

style, than the photo he started from. That is not the end of the

fair-use inquiry. The test, recall, has four parts, with one

focusing squarely on Goldsmith's interests. But factor 1 is

supposed to measure what Warhol has done. Did his "new work" "add[

] something new, with a further purpose or different character"?

Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579. Did it "alter[ ] the first with

new expression, meaning, or message"?

Ibid. It did, and it

did. In failing to give Warhol credit for that transformation, the

majority distorts ultimate resolution of the fair-use question.

Still more troubling are the consequences of today's ruling for

other artists. If Warhol does not get credit for transformative

copying, who will? And when artists less famous than Warhol cannot

benefit from fair use, it will matter even more. Goldsmith would

probably have granted Warhol a license with few conditions, and for

a price well within his budget. But as our precedents show,

licensors sometimes place stringent limits on follow-on uses,

especially to prevent kinds of expression they disapprove. And

licensors may charge fees that prevent many or most artists from

gaining access to original works. Of course, that is all well and

good if an artist wants merely to copy the original and market it

as his own. Preventing those uses-and thus incentivizing the

creation of original works-is what copyrights are for. But when the

artist wants to make a transformative use, a different issue is

presented. By now, the reason why should be obvious. "Inhibit[ing]

subsequent writers" and artists from "improv[ing] upon prior

works"-as the majority does today-will "frustrate the very ends

sought to be attained" by copyright law.

Harper & Row,

471 U. S., at 549. It will stifle creativity of every sort. It will

impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the

expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It

will make our world poorer.